Terry Rodgers — Dimensions of Ambiguity

The blessing and curse of sex appeal —

You just might get what you ask for

By Eva Karcher

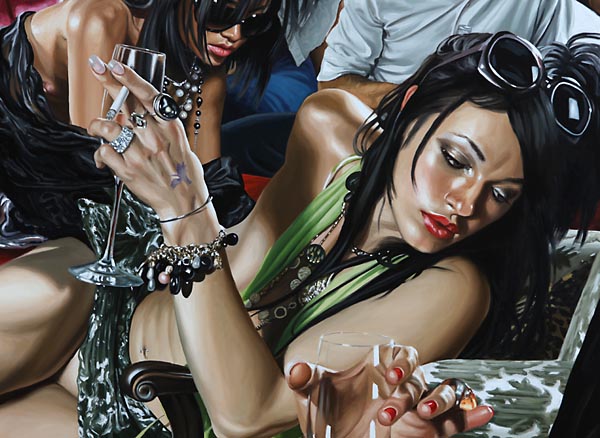

It is always an ego party. Perfect-bodied people reflect each other with cool narcissism, displaying fine breasts and washboard stomachs to each other, playing with the carefully rehearsed refinement of their seductive power. Women as well as men celebrate themselves as glamour toys, the hair, long black locks, or silky blond manes, the lips appetent and full, with a mother of pearl gleam, the teeth sparkling white. Champagne or the après-cigarette in the ringed hand, the acrylic nails French-manicured, heavy silver chains around the neck and hips, thin threads of gold around the ankles, the Rolex and the Patek Philippe on the wrist, G-strings and see-through bras, open silk shirts and thigh-high stockings, high heels and XXL glasses adorned with imitation diamonds: the stylization and maximization of their own potential to attract woos with perfected poses and gestures, but indeed turns into a self-constructed trap in keeping with these very optimised standards of beauty.

Because hedonism, if it becomes in such a blind way the single purpose in life, perhaps even becoming the placebo of one’s own right to exist, gives rise to emptiness. For more than 20 years, the American artist Terry Rodgers, who was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1947, and grew up in Washington, portrays in his paintings the rituals of consumerism, in which everything, bodies as well as goods, is charged with sex appeal. He conceives his highly virtuoso paintings as an allegory of all of the “dreams and longings, efforts and struggles, to be happy and to find love. We strive with all means possible for affection, to associate ourselves with others, and yet remain lonely.” No surprise, then, if the way to a happy ending, at least in the secularised western world, leads us almost exclusively towards the luxurious promises of capitalist dogma. But, then frustration is pre-programmed, according to Rodgers, “because you can buy things, but not a feeling of self-worth or harmony”.

However, it seems as if this peculiar alienation, resulting from the empty wealth of too much money, has come to an end. The worldwide financial crisis that broke out in the autumn of 2008 turns these decorative Boy-Toys and It-Girls into “Strangers in Paradise” (the title of a painting from 2008), not only on a material level but also on an ethical level. Suddenly, the aesthetic decadence of turbo capitalism no longer appears worthwhile. For, behind this shining façade, an ugly core of pure selfishness comes to light.

End of the party. End of the party? Rodgers himself always considers his paintings as atmospheric tableaux of an existentialist post-party-hangover mood. It has kept and keeps us trapped since we increasingly began to define ourselves through media images. For almost everyone does everything for the camera or the film lens – from diets and plastic surgery to torture and bestial murder. The endless manipulation of photographs and film stills is equalled by the manipulation of the bodies, inside and out. This mutual dependency, which in its extreme form almost necessarily creates perversion, is, according to Rodgers, conditioned by the total “fictionalisation of our culture”. It prevents imagination and fantasy rather than promotes them because, unlike literature, it conditions perception on a one-dimensional level and makes a direct communication with the senses impossible. No image can replace the discovery and feeling of closeness and warmth. So the more the virtualization of reality controls our very fragile actuality, the less a person living in this globalized society can still manage a direct, human communication.

Terry Rodgers’ slick-chic works have precisely this dilemma in view. While today’s stars and starlets – who create a production line of hopeful look-alikes – stage manage the correlation between being and illusion, the masses remain at the mercy of this illusion. They do indeed learn a few tricks of the trade from jungle camp and top model TV series, but there is scarcely any analytical distance involved. While their role models radiate as glittering symbols of their projections, they, the viewers themselves, remain objects, victims of the ubiquitous media machinery.

“This is why I compose my paintings as still lives of temptation. There is always too much of everything, accessories, drugs, desire, beauty.” But overabundance, as Rodgers shows in his paintings, is a wholly ineffective prescription against unbounded hedonism.

He finds his models everywhere, in restaurants, clubs, airports and streets. Some detail in their faces, their figures, inspires him. He approaches them, invites them to his studio, lets them try on clothes, draws them and at some point drafts the picture crystallizing in his imagination. Then his assistant paints a first, rough colour version in acrylic, before the artist, working for weeks, and sometimes months, applies layer upon layer of translucent oil. He works on up to ten works at the same time, and he does so with the bravura of an old master. It is no coincidence that Diego Velászquez and Otto Dix, the genius of the New Objectivity of the 1920s, are among his role models, but also Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, “because of the delicacy of their vision”.

But his protagonists lack this grace, because it requires more than fitness, namely devotion and soul. In the “post-erotic” era, in Rodgers’ characterisation, sex is gladly celebrated without feeling, like a sophisticated cocktail. Nothing wrong with that, but over the long-term it is dismally unsatisfying.

Terry Rodgers’ paintings show this vacuum as an imbalance “of standards, as everyone, not just western society, defines them”. Fundamentalist ideologies, whether driven by religion, ethnicity, politics or, as in the western world, capitalistic-hedonism, tear up the delicate balance of inner integrity. Instead of making values absolute, regardless of whether they belong to Mammon or an orthodox canon of belief, we should all dare to love more.