Unseen

By Jim Zimmerman

Terry Rodgers beckons us into a world of profusion and unreal “reality,” filled with pristine bodies and luxurious settings. At first glance, what seems to be a projection of our longing for opulence and hedonism is in fact a complex scenario that raises questions about interdependence, desire, separation, and the profound difference between solitude and isolation.

The fictions of our real lives are delicately indicated in the tableaux Rodgers creates, populated with imaginary characters who are grounded in the flesh and bone of models, and recorded with a power and sensitivity rare in contemporary painting. There is an invisible presence pervading these works, something that can be sensed but not defined, a force that communicates itself by a slight disturbance in every human figure.

From spectacular large canvases and stark photo-portraits to kaleidoscopic videos, Rodgers has shown us alone and alone together, seeking or avoiding one another, always transfixed by something just beyond our ken. Rodgers’ work both collapses and emphasizes psychic distance and physical proximity. It suggests that, in a world of ready-made entertainments, there’s an underlying uncertainty and a sense that something is missing.

The vectoral dynamics that Rodgers is known for continue to provide rich and suggestive possibilities about these freighted moments captured in resplendent scenes. It is possible that the figures are caught between purposeful moves, with a specific objective in mind, a reason for their motion. And yet this stasis may indicate that these characters are perhaps caught by what is going on in their own heads.

The notion of hearing voices is not just confined to disturbed people. We all have voices in our heads, but we are often uncertain about their origins. Parents may seem to be present, their unforgettable words echoing down the years, a recurrent source of the silent verbalizations that reside in our own minds, linked so powerfully to invisible sources. Then there are snippets of the printed word, and fragments of phrases or voices from media—films, songs, poetry slams, a bit of forgotten talk—that pour in on us. But, among the cacophony, where is our own unique inner voice, if there is such a thing? How can we separate it from the commotion that seems to have its unseen sources far outside of us?

All of this contributes to primal fears: fear of ourselves, and fear of each other. And such fears multiply themselves and divide us, resulting in a compulsion to seek a safe hiding place. The architecture of isolation may be a realm of dream, or nightmare, ever an unknown sphere where we can no longer see each other or even see ourselves.

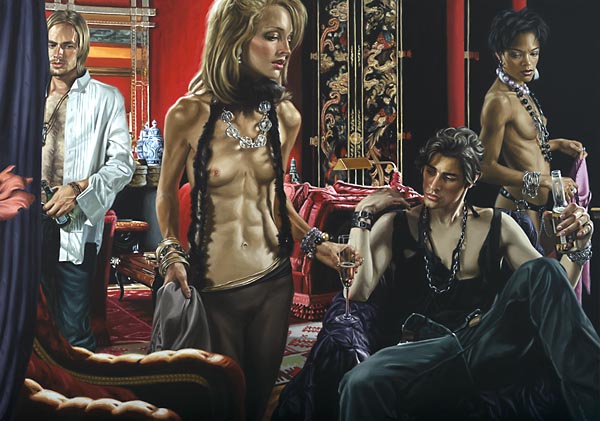

In the case of many of the paintings, the facial, gestural, and postural indicators of the figures suggest that these individuals are each listening to something unique to them, something deeply and perhaps darkly internal. In The Architecture of Light, for example, the woman seems oblivious to the fact that someone might be approaching her, and instead of seeing anything herself, her eyes evince an inward gaze, a listening look. Similarly, in Mise-en-scene, all four figures are caught in a moment of interiority. They look a little lost.

In fact, “lostness” pervades Rodgers’ works, which are rich and occasionally intimidating in their complexity. They can push us past that comfort we sometimes seek in art. One might ask, “What are these wild-seeming parties?” And yet, after a minute’s concentrated contemplation, the multiplicity of “solo spaces” within the paintings comes into focus. Each canvas, though integrated by subtle compositional features, contains a dozen or more local “beacons,” where the figures and the objects draw us in, and we can rest for a moment in the pleasure of the paint.

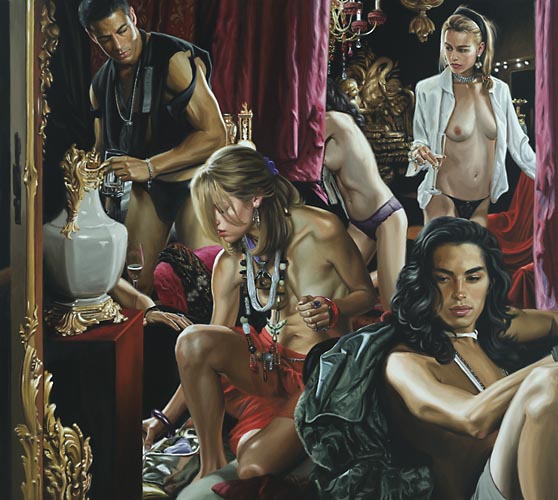

In Immaculate Reflection, at first we are drawn to the apparently reflective trio of figures, with an unseen fourth. Eyes downcast, caught in the midst of some absorbing private moment, these figures are unable to apprehend each other, perhaps unable even to apprehend themselves. It is an invitation to reflect on this dense scene of material comforts and exotic fashion where, if we were to find ourselves, we might not know ourselves either. Is it a green room for models? Is it the aftermath of a guerilla design collaborative’s brainstorming session?

On further reflection, we begin to be more literal. We see what the painter has done with light: with reflections, refractions, and shadows. All of the shimmering, glimmering surfaces come alive as we glance from quadrant to quadrant in the piece. Glass, plastic, skin, shiny furniture, and jewelry all bounce light from their complex surfaces, almost, one could say, with joy.

In the same way that a sensational installation piece invites or even demands our engagement, seducing the viewer to move and interact with the work by experimenting with different points of view around and through the space, Rodgers’ intricate and elaborate compositions encourage our own participation, causing our eyes to follow the lines and, in the presence of the larger works, requiring actual physical movement, up close and back, side to side, up and down.

In Unseen, the tendency to be pulled forcefully into a vortex is most obvious. We plunge toward the central figure, as if a gravitational field irresistibly draws us in. And after some moments, we begin to pull back and appreciate, as our eye recedes, the surrounding figures and forces.

In Lux Perpetua and Beyond Decadence, no one in either of the two quintets is connecting. This is a frequent feature of Rodgers’ work: the moment of least human connection even in dense proximity. But viewed one by one, these figures take on a different air, as if the aloneness is in itself restful, reassuring, and the togetherness is what is most challenging or mystifying. Oddly, by absorbing their unease, we abruptly gain a moment’s peace.

Rodgers avoids irony, parody, and pastiche in favor of a generous, even spectacular presence, an overwhelming materiality that the players themselves are bowled over by. The viewer is lost from the beginning, and the challenge is to orient ourselves. We are not accustomed to this feeling. With advancing technology, we can increasingly manage to feel that we know everything that is going on, and that we are never alone even when we are all by ourselves. We can simulate having many friends even as we choose to have no social life at all.

In a time like this, the artist working in a traditional medium must be brave, bold, committed, and refuse to bow to the trends and tastes and fads and fashions. The dialectics of art promise that styles are renewed and recombined, remixed and hacked and remediated until they come back to us as novelties.

Those who wish to find art historical nuggets in Rodgers’ works are rewarded for their efforts, but Rodgers himself is not encouraging the activity. He downplays the presence of such things: “Referencing for referencing’s sake is like name-dropping. There’s no value in it unless it somehow enhances the artwork is question.”

In the case of Unseen, Rodgers playfully suggests, “There’s this slight ringing in our ears, an unspoken something. It’s a strange cross between the present and something allegorical from the visual past.”

Indeed, there is something dynamic in the scene, a notion of motion associated with the gesture of the central woman. Although Rodgers insists that he is not referencing Michelangelo’s Dawn, Titian’s Danae, or Luca Giordano’s Venus and Mars, he admits to “some strange connection to that painterly mythology.” The painting is richer and more complex because of a movement and a feeling delicately suggested.

Rodgers observes, “When it works, you feel some implication that you can’t place, a subtle resonance. It’s as if the story is just a little bigger than the details on the canvas.”

Ultimately, any search for clues distracts us from what turns out to be the most remarkable aspect of the work: the free-flowing brushstrokes that, attentively observed, offer a delightful painterly exhibition of technique. Dominant recognizable images, once fully assimilated, if that is possible, then give way to a journey through color and contrast and line.

The precision of Rodgers’ work creates vivid, striking, irresistible images. The loose painting gets lost on first glance, but it is one of the many pleasures one experiences when spending time among the paintings. By bombarding the viewer with innumerable particulars, exquisitely drawn, frequently erotic, and often also whimsical, Rodgers tantalizes us with the play of light on texture.

We love mysteries, we think we do, but we only really love the ones that can be solved, that are able to reach some kind of resolution, the aha, I get it, it’s done, it’s over, good triumphs over evil, order is restored. But the completely enigmatic aspects of life trouble us. Little and large alike, the simple daily questions of what to do, when, and with whom are much less happy for us, and we are more uneasy with them because they nag at us and won’t go away.

Rodgers’ work can make us uneasy because we want to figure out what is going on, we want to get it. We want to interpret, comprehend, and finally satisfy ourselves that we know “what is really going on.” What is in fact going on is the same set of minor mysteries we face every day and throughout our lives. We are constantly in the throes of not knowing what is going on.

Great art re-minds us. It rearranges our thought process, scrambles the contents ever so slightly, and refreshes our senses. We mine an artwork for something not visible in the everyday world—and yet these unseen variables are the very constituents of the quotidian. A work of art sometimes succeeds in relieving us of our tensions and fears, of our obsessive attempt to control every little thing, by temporarily alarming us. We do not know what to make of it. That is the human condition, to fail and fail, and to be aware of it. The most noble ones among us have managed a lightness of being in the face of the misery and horror. Rodgers’ work enhances the hopeful mystery of consciousness, and highlights the majesty of our individual failures.

2017